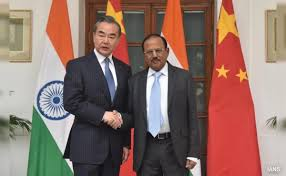

The two Special Representatives (SRs) on the India-China boundary issue met in Beijing this week. This was the first such meeting between Ajit Doval and Wang Yi in five years. The agreement to hold this dialogue was one of the outcomes of the meeting between Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi and Chinese President Xi Jinping in Kazan in October 2024.

However, in Kazan, there was no specific timeline that had been spelt out for the SRs-level meeting. Back then, the Indian side had said that the two leaders agreed for the SRs to meet “at an early date”. The Chinese statement had not shown any such urgency. All it did was call for the two sides to “make good use” of the SR-level mechanism. Given this, it is important that the SRs have met before the end of the year. This is indicative of intent on both sides to begin moving forward on the long path to normalisation. That said, the readouts issued by the two sides following the Doval-Wang meeting show that while there is progress in picking the low-hanging fruit, fundamental issues remain to be resolved.

A Peculiar Malpractice By China

The Chinese side issued two readouts after the meeting. The first one talked about the discussions being held with a “positive and constructive attitude” and the two sides achieving a six-point consensus. The second one detailed the remarks by Wang and Doval. There has been some discussion and consternation within the Indian media about the verbose nature of the Chinese readouts in comparison to the more business-like statement by the Ministry of External Affairs. For anyone following Chinese diplomacy and the way the Ministry of Foreign Affairs sets the narrative on issues, this is not out of the ordinary. In fact, this discussion offers an opportunity to highlight a few noteworthy aspects of China’s narrative diplomacy.

First, China’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs tends to be rather quick in publishing its account of meetings with foreign leaders and officials. In a fast-paced, 24X7 media environment, this allows it to set the terms of discourse. Second, meeting readouts issued by the ministry often tend to detail the remarks by the Chinese representative along with those by the other side. Of course, in representing the other side’s views, the readouts tend to be extremely selective. This is peculiar malpractice by Beijing, which is primarily designed for domestic consumption. However, it does have broader implications. For instance, one of the Chinese readouts after the Doval-Wang meeting quotes Doval as saying that “over the past five years, with the joint efforts of both sides, relevant issues in the border area have been properly resolved”. This comment is not echoed in the MEA’s version of the meeting. In addition, the ground situation in Eastern Ladakh indicates that all issues have not been resolved. It is, therefore, imperative for other governments to act with greater speed and clarity in the narrative domain when engaging with China.

Where The Two Agree

Further comparing the readouts issued by both sides after the SR-level meeting, one can identify some areas of commonalities. For instance, both sides confirmed forward movement with regard to the Kailash Mansarovar Yatra, data sharing on trans-border rivers and border trade. This is the immediate and tangible outcome of the meeting. One must watch for the implementation of these decisions. The two sides also agreed on the importance of “stable, predictable and amicable/sound India-China relations”. This is a shared strategic assessment.

Most significantly, one of the Chinese readouts said that both sides “agreed to further refine the management and control rules in the border area, strengthen the building of confidence-building measures (CBMs), and achieve sustainable peace and tranquility on the border”. The Indian readout echoed this, saying that the two sides “discussed various measures to maintain peace and tranquillity on the border and advance effective border management. They decided to use, coordinate and guide the relevant diplomatic and military mechanisms towards this purpose.” Given the changes in the facts on the ground over the past few decades owing to shifts in patterns of force deployment and border settlements, infrastructure development by both sides and technological changes, which have enhanced situational awareness and response capabilities, it is useful to have fresh dialogue on CBMs and border management protocols.

Difference In ‘Urgency’

Along with this, it is useful that the statements from both sides have referenced the need for a final settlement of the boundary issue. The MEA’s readout said that the two sides “reiterated the importance of maintaining a political perspective of the overall bilateral relationship while seeking a fair, reasonable and mutually acceptable framework for settlement of the boundary question and resolved to inject more vitality into this process”. The Chinese readout talked about the need to “continue seeking a package of solutions to the boundary question that is fair, reasonable and acceptable to both in accordance with the political guiding principles reached in 2005”. There is a distinct difference in terms of the urgency that is conveyed in the language used by the two sides on the issue of settlement. It is important for the SR-level talks to begin moving in the direction of a framework for resolution, which is their primary mandate. Tangible steps in this direction, such as Beijing agreeing to exchange claim details and maps, would go a long way in building trust.

An Overall Resolution Is Important

But it doesn’t seem that this is imminent. The Indian and Chinese sides continue to hold very different views on the positioning of the boundary issue in terms of the overall relationship. The MEA’s readout said that “both SRs underlined the importance of maintaining peace and tranquillity in the border areas to promote overall development of the India-China bilateral relationship. They emphasised the need to ensure peaceful conditions on the ground so that issues on the border do not hold back the normal development of bilateral relations.” In contrast, the first Chinese readout said that both sides agreed that “the border issue should be properly handled from the overall situation of bilateral relations so as not to affect the development of bilateral relations”. This can be read in a couple of ways. But the subsequent readout makes the Chinese perspective clear. It quoted Wang Yi as saying that the two sides should “invest their precious resources in development and revitalization” and “place the boundary question in an appropriate position in bilateral relations”, while “promoting China-India relations to return to a track of healthy and stable development at an early date”.

Such compartmentalisation of the relationship is, frankly, untenable politically. New Delhi should continue to insist that Beijing view the relationship from an overall perspective and work not only to maintain peace and tranquillity along the border but also actively seek a resolution.