Kalpit A Mankikar

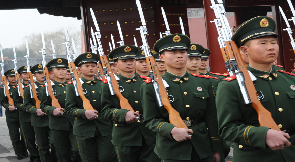

The Communist Party of China (CPC) recently purged two former defence ministers—Li Shangfu and Wei Fenghe—in the wake of the Central Military Commission (CMC) conclave held in Yan’an. The Party has accused Li Shangfu of making payoffs for promotions and pocketing bribes. Wei, who was the Defence Minister at the time of the 2020 Galwan clashes on the India-China border, was found guilty of disloyalty and betraying the trust of the CPC, vitiating the political environment of the People’s Liberation Army (PLA). Li and Wei are the senior-most military figures to be purged in the recent years. Li was ousted from his post in October 2023, making his tenure in the defence ministry one of the shortest in recent times. The shunting off of senior military figures comes along with new appointments, which points to the cementing of the Party within the army. Take the instance of He Hongjun, who has been appointed General. General He serves on the CPC’s Central Committee and was, till recently, executive deputy director of the Central Military Commission (CMC) Political Work Department, which is primarily responsible for tasks like party-building and political education within the military.

There seems to have been significant concern on the issue of graft within the military, and its impact on war preparedness. Earlier this year, senior figures from the PLA and technocrats from the defence-industrial complex were ejected from China’s legislature over graft-related cases. Xi reconstituted the People’s Liberation Army Rocket Force, which is in charge of the nation’s nuclear arsenal, opening corruption probes against officers leading the unit.

A recent article in the PLA Daily emphasises that Xi’s anti-turpitude drive led to the unravelling of hidden graft amongst cliques of corrupt commanders. The issue boomed at the recent Central Military Commission political conference that Xi convened in Yan’an. In his speech to CMC top brass and PLA commanders at the conclave, Xi assessed that the world collectively and nations individually faced intricate challenges, which even the PLA would have to grapple with. He underscored that the military could not afford to have corrupt elements, and that it was a top priority to eliminate corruption. He advocated for greater scrutiny of departments involved in defence production by anti-corruption investigators, and unearthing new forms of corruption. As head of the CMC that oversees the military, Xi drove home the need for rectification within the ranks. He emphasised that the Party’s strength came from the PLA’s organisational unity, and that the ‘gun’ (meaning the military) must be in the hands of those faithful to the Party. Looking forward, the Party’s objective is to boost the PLA’s capability to prepare for war, along with better integration of its leadership into every sphere of combat-readiness. He reinforced that the aim was to build a strong military by 2027, which is when the PLA marks its centenary.

A commentary published on China’s Ministry of National Defence credited Xi for dealing with the issue of lax discipline within the PLA that had existed from the tenures of his predecessors. The article argued for more stringent oversight systems, referencing Mao Zedong’s Yan’an Rectification campaign, highlighting that revolutionary victory was incumbent on discipline within the ranks. The Yan’an Rectification campaign of the 1940s aimed to primarily boost the Party’s ideological quotient, with cadres and leaders studying the writings of Mao. Historians argue that the Yan’an campaign led to voices critical of Mao being sidelined within the Party. The violent campaign led to around 10,000 deaths but also to Mao cementing his hold over the Party.

These internal developments in China’s elite politics come at a time when serious tensions have developed between China and its neighbours. The PLA launched military exercises near Taiwan following the election of President Lai Ching-te. China is also engaged in a standoff against the Philippines over some maritime features in the South China Sea. It has been nearly four years since China started amassing a large force along the Indian border, following repeated attempts by the PLA to change the status quo along the Indo-China border.

It is evident that there has been a well-crafted initiative in China’s domestic narrative to put a shine on Xi’s role in the PLA’s transformation as a modern force, which has been projected as his signature initiative. CMC vice-chairperson General Zhang Youxia asserted in an article in the People’s Daily that the military had been vulnerable to risks before Xi took over in 2012 and that he presided over the task of rebuilding the army and ridding it of corrupt generals. There is an implied suggestion in this assertion that Xi’s predecessors were lax in imposing discipline in the armed forces, which led to weaking national security. It may be recalled that there was a purge of CMC top brass Guo Boxiong, Xu Caihou and other senior military figures shortly after Xi assumed office on the charges that they had been responsible for accepting bribes in exchange for handing out promotions in the armed forces.

The downfall of senior figures in the defence establishment uncovered the extent of the practice of buying ranks in the services, which has put a question mark on the combat readiness of one of the world’s largest armies. The purge of Wei and Li flies in the face of this narrative and reflects poorly on Xi’s judgment, since the men he picked to replace the previous lot are also mired in corruption charges. The recurrent purges of senior military officials point to a strained relationship between the Party and the PLA, which may be exacerbated by further investigations into other units of the military. By appointing military leaders who are proficient in the CPC’s ideology to senior ranks, Xi may be trying to paper over the cracks.