Early last year, Sri Lanka declared bankruptcy and the possibility of defaulting on sovereign debt repayment. The island nation’s crisis has been in the making since 2015 following a major bond scandal, thus diluting the credibility of the Central Bank. For the past two decades, Sri Lanka has been borrowing large amounts from the International Monetary Fund (IMF), China, India, and Japan to finance infrastructure projects in the country, subsequently increasing debt unsustainability and slipping into precarious macroeconomic dynamics. Hands full with high-interest debt repayments and the most prominent political blowout in its history, the government’s faulty decision towards a 100-percent organic farming policy and ban on the use of imported fertilisers that led to a 50-percent drop in agricultural output, permanently sealed the fate of the nation. As supply dwindled, the price of food skyrocketed, thus forcing the government to import even essential dietary commodities like rice, wheat, and lentils.

To be sure, global events have played a hand in Sri Lanka’s costly misfortunes. The COVID-19 pandemic left a scar on the nation’s booming tourist sector, which accounts for 12.6 percent of the nation’s GDP and the third largest source of its foreign income, further aggravated by the memories of the 2019 Easter Bombings. Moreover, the disastrous impact of the Ukraine-Russia war has exacerbated the food and fuel crisis in the island nation by raising the price of crude oil and shrinking the volume of tourists from the former nations. China, which contributed the third highest number of tourists to Sri Lanka, is dealing with a health crisis now. Widening fiscal deficits, depleting foreign exchange reserves, and a depreciating currency have led to unchecked inflation and the worst economic downturn since its independence from the United Kingdom (UK) in 1948. What ensued triggered a political washout and the end of an era ruled by the powerful Rajapaksas.

Debtor in Despair: Sri Lanka, China, and the IMF

After months of deliberation, Sri Lanka and the IMF reached a staff-level agreement under the Extended Fund Facility (EFF) for about US$2.9 billion conditional on financial backing from its multilateral creditors, including India and China, in early September 2022. In addition to support from its biggest bilateral lenders, the bailout package would require Sri Lanka to promise to restructure its economic policies and reach a final consensus among all its stakeholders. In a much-needed show of support, India pledged to help the crisis-stricken island nation with its debt restructuring plan based on Debt Sustainability Analysis (DSA). China, Sri Lanka’s biggest creditor at US$ 7.4 billion or nearly a fifth of its public external debt—has reportedly given the green signal for the requisite financial assurance. However, Beijing still has differences over the loan moratorium period and other terms of debt structuring with the IMF’s executive board.

Gradually but successfully ousting the IMF as the developing world, especially South Asia’s most enormous lending body, China has inched its way into the global development space by disbursing loans to financially ailing nations such as Sri Lanka and Pakistan that have hit rock-bottom and had earlier accepted it’s terms under the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI). This has made other creditor countries increasingly wary of Chinese influence on states who have partnered with the Asian Giant under its contentious schemes.

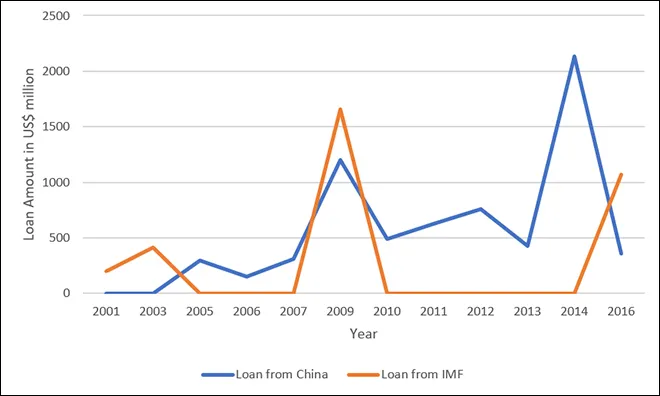

Figure 1: Comparing Sri Lanka’s external debt proportions (2001-2016)

Under the much-disputed BRI, the Chinese government offers concessional loans and grants to partner states for infrastructural development—a commitment that Sri Lanka now finds itself unable to honour. Following a balance of payment crisis in 2017 the island nation approached China, only to be refused by the latter because they couldn’t be seen bequeathing favours to a single ally. In 2023, China is in a difficult situation, it has a full-blown health crisis on its hands, and the global economy (18 percent of which comprises China) is set to note a reduced growth rate of 2.7 percent this year. The effects of a global economic slowdown and the backfiring of the zero-covid policy will lead to reduced revenues for China as it halts all production and manufacturing activities to deal with the virus. As anticipated, Sri Lanka’s requests for currency swaps and financial assistance from China have fallen on deaf ears.

A road to recovery: Urgent financial rescue

On 5 December 2022, the World Bank (WBG) confirmed that Sri Lanka had reverse graduated, and would be eligible for funding from the International Development Association (IDA). The WBG elaborated on its commitment to helping Sri Lanka out of the crisis and providing concessional finance, technical assistance, and policy advice to the state. While most of Sri Lanka’s debt accrues to borrowings from the West, China seals its spot as the nation’s most significant bilateral creditor at 12 percent of its outstanding foreign debt. Borrowings from China are much higher if the borrowings from Chinese policy banks are to be accounted for; Sri Lanka loaned US$ 4.3 billion from China’s Exim Bank and US$ 3 billion from China Development Bank, putting borrowings from the former at 19.6 percent of the total outstanding foreign debt.

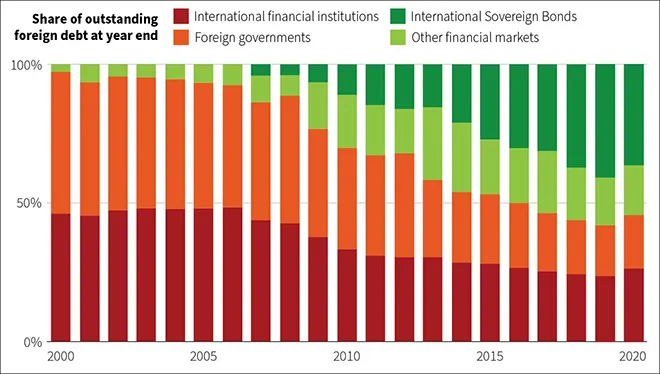

On the other hand, 80 percent of the outstanding financial debt owed to the West, its allies, the World Bank and the Asian Development Bank is held in the form of International Sovereign Bonds and a substantial amount as market borrowings to Western vulture hedge funds—the central ones being BlackRock (US), Ashmore Group (Britain), Allianz (Germany), UBS (Switzerland), HSBC (Britain), JPMorgan Chase (US) and Prudential (US). It is perplexing, therefore, to see that an active effort to schedule debt restructuring talks and considering a substantial amount of debt is owed to the West, it is unfitting that they haven’t made an active effort to schedule debt restructuring talks and provided financial assurances shifting the entire burden of securing assurances to a nation that is miserably bogged down by political turbulence and economic uncertainty.

Figure 2: Sri Lanka’s Foreign Debt Distribution

Meanwhile, Sri Lanka awaits a response from its trading partners and is working out the kinks (conditional austerity measures include selling off state-owned enterprises, reducing government jobs and increasing taxes) to ensure that IDA sanctions the US$2.9 billion loan at the earliest. While India can do little to hasten the process, the crisis also presents the perfect opportunity for India to cement its position as Sri Lanka’s strategic all-weather ally and ameliorate its turbulent diplomatic relations with the island nation.