Six years after Indian and Chinese soldiers faced off in Doklam, Bhutan’s Prime Minister has said Beijing has an equal say in finding a resolution to the dispute over the high-altitude plateau which New Delhi believes has been illegally occupied by China.

”It is not up to Bhutan alone to solve the problem,” said Prime Minister Lotay Tshering in an interview with the Belgian Daily La Libre. ”There are three of us. There is no big or small country, there are three equal countries, each counting for a third.”

The Bhutanese Prime Minister’s statement on China having a stake in finding a resolution to the territorial dispute is likely to be deeply problematic for New Delhi, which is entirely opposed to China extending its footprint in Doklam since the plateau lies close to the sensitive Siliguri corridor, the narrow tract of land that separates India’s Northeastern states from the rest of the country.

Now, Bhutan’s Prime Minister says, ”We are ready. As soon as the other two parties are ready too, we can discuss.” It is an indicator that Thimphu is willing to negotiate the status of the tri-junction in Doklam between India, China and Bhutan, which lies at the heart of the dispute.

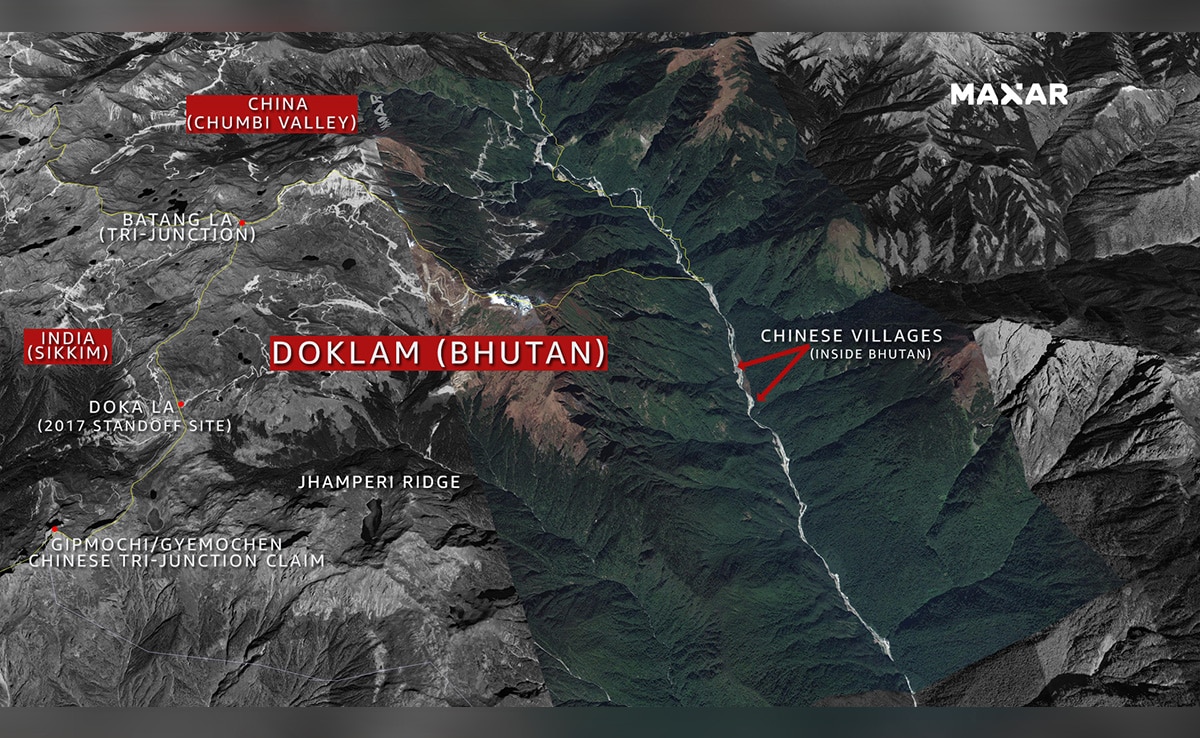

Mr. Tshering’s statement is in stark contrast with what he had told The Hindu in 2019, that ”no side” should do anything near the existing trijunction point between the three countries ”unilaterally”. For decades, that trijunction point, as reflected in international maps, lies at a spot called Batang La. China’s Chumbi Valley lies to the North of Batang La, Bhutan lies to the South and East and India (Sikkim), to the West.

China wants that tri-junction to be shifted approximately 7 km south of Batang La to a peak called Mount Gipmochi. If that were to happen, the entire Doklam plateau would legally become a part of China, a move not acceptable to New Delhi.

In 2017, Indian and Chinese soldiers were involved in a tense standoff lasting more than two months when Indian soldiers entered the Doklam plateau to prevent China extending a road that it was illegally constructing in the direction of Mount Gipmochi and an adjoining hill feature called the Jhampheri ridge. The Indian Army is clear – the Chinese Army cannot be allowed to crest Jhampheri as that would give them a clear line of sight to the Siliguri corridor.

“Any attempt of China to shift the location of the tri-junction South would be unacceptable to the Indian Armed Forces. Chinese attempts at unilateral disruption of the status quo, like construction activity across parts of Western Bhutan, is a major security concern with a clear security bearing upon India,” said (Retd) Lieutenant General Pravin Bakshi, who was Eastern Army commander when the Doklam crisis erupted in 2017.

Since 2017 when the Chinese agreed to back off from the face-off site at Doklam, they have carved into Bhutanese territory along the Amo Chu river valley, which lies adjacent and directly to the East of Doklam. Here, they have constructed several villages and a road directly through territory that has always been a part of Bhutan, as evident in official maps of the country. Satellite images with details of this construction have been extensively reported by NDTV.

Now, however, in the clearest indication that Bhutan may have been forced to cede territory to China, Prime Minister Lotay Tshering says, ”A lot of information is circulating in the media about Chinese facilities in Bhutan. We are not making a [big] deal about them because they are not in Bhutan. We have said it categorically, there is no intrusion as mentioned in the media. This is an international border and we know exactly what belongs to us.”

Mr Tshering’s remark is a likely reflection of the fact that Thimpu can do little to halt China’s ‘salami-slicing’ of Bhutanese territory, not just along its Western frontiers near Doklam but also to the North of the country in the Jakarlung and Pasamlung Valleys. The Western areas measure approximately 270 square km while disputed areas to the North measure nearly 500 square km.

”The Bhutanese PM’s statement suggests that to save face, Bhutan is claiming that the territories China has stealthily occupied are not Bhutanese areas,” says Dr. Brahma Chellaney, India’s foremost strategic affairs expert on China. ”But this could encourage further Chinese salami slicing of Bhutanese territories.”

New Delhi:

Six years after Indian and Chinese soldiers faced off in Doklam, Bhutan’s Prime Minister has said Beijing has an equal say in finding a resolution to the dispute over the high-altitude plateau which New Delhi believes has been illegally occupied by China.

”It is not up to Bhutan alone to solve the problem,” said Prime Minister Lotay Tshering in an interview with the Belgian Daily La Libre. ”There are three of us. There is no big or small country, there are three equal countries, each counting for a third.”

The Bhutanese Prime Minister’s statement on China having a stake in finding a resolution to the territorial dispute is likely to be deeply problematic for New Delhi, which is entirely opposed to China extending its footprint in Doklam since the plateau lies close to the sensitive Siliguri corridor, the narrow tract of land that separates India’s Northeastern states from the rest of the country.

Now, Bhutan’s Prime Minister says, ”We are ready. As soon as the other two parties are ready too, we can discuss.” It is an indicator that Thimphu is willing to negotiate the status of the tri-junction in Doklam between India, China and Bhutan, which lies at the heart of the dispute.

Mr. Tshering’s statement is in stark contrast with what he had told The Hindu in 2019, that ”no side” should do anything near the existing trijunction point between the three countries ”unilaterally”. For decades, that trijunction point, as reflected in international maps, lies at a spot called Batang La. China’s Chumbi Valley lies to the North of Batang La, Bhutan lies to the South and East and India (Sikkim), to the West.

China wants that tri-junction to be shifted approximately 7 km south of Batang La to a peak called Mount Gipmochi. If that were to happen, the entire Doklam plateau would legally become a part of China, a move not acceptable to New Delhi.

In 2017, Indian and Chinese soldiers were involved in a tense standoff lasting more than two months when Indian soldiers entered the Doklam plateau to prevent China extending a road that it was illegally constructing in the direction of Mount Gipmochi and an adjoining hill feature called the Jhampheri ridge. The Indian Army is clear – the Chinese Army cannot be allowed to crest Jhampheri as that would give them a clear line of sight to the Siliguri corridor.

“Any attempt of China to shift the location of the tri-junction South would be unacceptable to the Indian Armed Forces. Chinese attempts at unilateral disruption of the status quo, like construction activity across parts of Western Bhutan, is a major security concern with a clear security bearing upon India,” said (Retd) Lieutenant General Pravin Bakshi, who was Eastern Army commander when the Doklam crisis erupted in 2017.

Since 2017 when the Chinese agreed to back off from the face-off site at Doklam, they have carved into Bhutanese territory along the Amo Chu river valley, which lies adjacent and directly to the East of Doklam. Here, they have constructed several villages and a road directly through territory that has always been a part of Bhutan, as evident in official maps of the country. Satellite images with details of this construction have been extensively reported by NDTV.

Now, however, in the clearest indication that Bhutan may have been forced to cede territory to China, Prime Minister Lotay Tshering says, ”A lot of information is circulating in the media about Chinese facilities in Bhutan. We are not making a [big] deal about them because they are not in Bhutan. We have said it categorically, there is no intrusion as mentioned in the media. This is an international border and we know exactly what belongs to us.”

Mr Tshering’s remark is a likely reflection of the fact that Thimpu can do little to halt China’s ‘salami-slicing’ of Bhutanese territory, not just along its Western frontiers near Doklam but also to the North of the country in the Jakarlung and Pasamlung Valleys. The Western areas measure approximately 270 square km while disputed areas to the North measure nearly 500 square km.

”The Bhutanese PM’s statement suggests that to save face, Bhutan is claiming that the territories China has stealthily occupied are not Bhutanese areas,” says Dr. Brahma Chellaney, India’s foremost strategic affairs expert on China. ”But this could encourage further Chinese salami slicing of Bhutanese territories.”

It is unclear if Bhutan is willing to hand over territory it has lost on its Western frontier in an effort to retain the areas to the North. Any move to legitimise Chinese control of Bhutanese territory to the West would be directly against India’s security interests.

In January this year, Chinese and Bhutanese experts met in Kunming and agreed to work towards reaching an agreement on their boundary talks. Both sides have held more than 20 rounds of talks so far and are reportedly working to arrive at a ‘positive consensus’. ”We are not experiencing major border problems with China, but some territories have not yet been demarcated,” said Prime Minister Tshering, downplaying the extent of China’s intrusions. ”After one or two more meetings, we will probably be able to draw a dividing line.”

New Delhi will be closely watching where that line is placed on a map.