The Indo-Pacific region offers enormous economic opportunities, both at the product and factor markets—as the region approximately comprises of as many as 38 countries, accommodating 65 percent or 4.3 billion of the world population, and accounts for 63 percent of the world GDP. In fact, above 50 percent of the world’s maritime trade occurs in this region. One of the major developments in the Indo-Pacific has been an increased vigour in intra-region partnerships within countries in the Indo-Pacific, and also with extra-regional actors to offset the intensifying presence of China.

There is no doubt that Beijing has strengthened its economic ties with the Indo-Pacific nations over the years. Countries such as Australia, South Korea, and Japan run a trade surplus against China, while India and Singapore run a trade deficit. In addition to enjoying a trade surplus, Australia, South Korea, and Japan has China as their largest trading partner, and exports to China contributes significantly to their own economies. Therefore, despite political hiccups, it is extremely important for these countries to maintain economic harmony with Beijing—so that there is no consequential decline in Chinese demand for their commodities.

One of the major developments in the Indo-Pacific has been an increased vigour in intra-region partnerships within countries in the Indo-Pacific, and also with extra-regional actors to offset the intensifying presence of China.

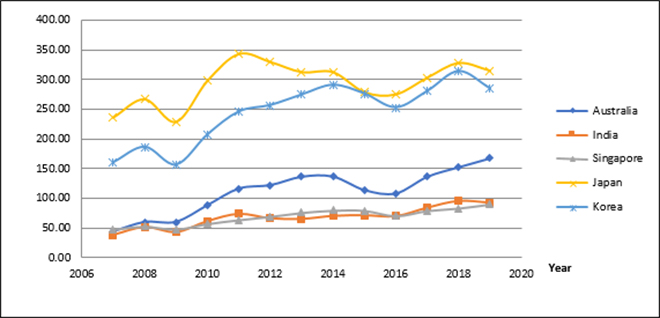

China has always had a high trade volume with the major Indo-Pacific countries, and this has been rising; as can be seen in the following figure, the trend has been positive in the last one-and-a-half decades. There have been very few instances of any dip in this trend—the one in 2007–08 could be attributed to the Global Financial Crisis, which had gradually recovered by 2010.

Figure 1: China’s Trade Volume with the major Indo-Pacific countries (In billion USD)

China’s inextricable linkages with most of the Indo-Pacific nations can be attributed to the key position it holds in the regional value chains. This is one of the most important factors which impede the countries in this region in completely diversifying their trade and investments towards other countries in the West, by diverting China. For example, Australian agricultural products are heavily dependent on the Global Value Chains (GVCs), where a large amount of imports come from China. In fact, technologically advanced nations such as Japan and South Korea rely on China for manufacturing high-tech components required as inputs in the production of smartphones by companies such as Apple, Xiaomi, Lenovo, and Huawei—these components are mostly assembled in China and then supplied to other nations.

As China leads the world in terms of outward Foreign Direct Investments (FDI), there have been reflections of the same in the Indo-Pacific. The inward and outward FDI flow between China and the Southeast Asian countries is of much larger volume when compared with the flows between India and the countries in the region. Over the years, China has expanded its economic and political networks through the progression of its ambitious Belt and Road Initiative (BRI). BRI, which is often alleged to worsen the long-term debt situation for the recipient countries, has been a major issue in the developing and underdeveloped nations of Southeast Asia and Sub-Saharan Africa.

China’s inextricable linkages with most of the Indo-Pacific nations can be attributed to the key position it holds in the regional value chains.

The growing geopolitical and geoeconomic rivalry with China is one major factor propelling India’s pivot to the Indo-Pacific. Allegations of Beijing’s problematic handling of the pandemic, the military standoff between India and China in the last few years, imposition of an 80 percent tariff on Australian barley, and most importantly, the pandemic-induced supply-chain disruptions evolving out of China have triggered alterations in the economic dynamics between the Indo-Pacific nations. Even the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN), which has historically chosen to remain reserved on the subject of the Indo-Pacific—launched the ASEAN Outlook on the Indo-Pacific in 2019, signalling its intentions to take note of the dynamics unfolding in its own backyard.

As a major economy and regional player, India has been undertaking efforts to scale up its role in trade and connectivity in the Indo-Pacific. According to the study by Confederation of Indian Industries (CII) in 2020, India’s trade with the selected 20 economies in the Indo-Pacific has grown eight times since 2001. While India’s combined trade with these economies was US $33 billion in 2001, it increased to US $262 billion in 2020. However, for a multitude of reasons, India’s economic engagement and leadership in the Indo-Pacific remains limited. These include the homogeneity in the service sector, which is centred on IT industries; lagging FDI flows between India and the Southeast Asian nations; the lack of big multinational corporations in India that could integrate themselves at various parts of the regional supply chains.

BRI, which is often alleged to worsen the long-term debt situation for the recipient countries, has been a major issue in the developing and underdeveloped nations of Southeast Asia and Sub-Saharan Africa.

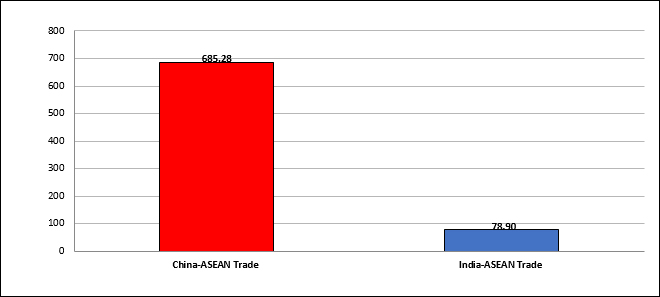

India’s economic performance in the region is hardly sufficient to counter the growing Chinese influence. While India outlines the ASEAN centrality as a core element in its Indo-Pacific strategy and tries to forge closer economic and strategic partnership with the ASEAN member states, India’s volume of trade with ASEAN is nowhere close to China as seen in the following figure. For the last 12 years, China has remained ASEAN’s largest trading partner and this year, ASEAN surpassed the European Union to become China’s largest trading bloc.

Figure 2: China-ASEAN Trade versus India-ASEAN Trade, 2020-21 (in Billion US$)

Boosting India’s economic ties with ASEAN has particular significance in enhancing India’s economic stature in Southeast Asia and the broader Indo-Pacific since economic leverage over Southeast Asia helps China concretise its position in the region. While the aggressive rise of China remains the Southeast Asian countries’ major strategic and security concern, benefits of prosperous trade with Beijing makes most Southeast Asian countries’ think twice before taking any decision that may annoy Beijing. Even other countries, which are at the forefront of coalitions against Beijing like Australia, Japan, and South Korea also fall in the same category. While these countries view China as a critical threat to their security and territorial integrity, trade ties make these nations economically dependent on China.

While the aggressive rise of China remains the Southeast Asian countries’ major strategic and security concern, benefits of prosperous trade with Beijing makes most Southeast Asian countries’ think twice before taking any decision that may annoy Beijing.

Therefore, to gain strategic prominence in the Indo-Pacific space, it is imperative for India to enhance its own economic capability and scale up its regional integration efforts. As the Indian economy is still not in a position to compete with the technologically advanced economies like South Korea and Taiwan, joining any trade agreement may hamper the domestic industries from collapse due to the flow of cheaper imports from other countries as part of the trade agreements. Given this, the challenge for India is to find a fine balance between the two.